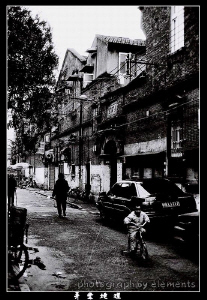

Architecture, especially residential architecture, is the mirror of social life. In old Shanghai those who could live in a longtang house could only be people with a fixed income. They had to be able to pay the monthly rent and tax for the house, in this case called the police tax. In the foreign concession, if people failed to pay, they had to move out right away. Since society was divided into different strata, the longtang houses were also classified into high, medium and low ranks. Different ranks of longtang houses were indeed differentiated by quality of construction, but moreover they were differentiated by location. The longtang houses in Zhabei and Nanshi Districts were the lowest in rank, while those in Hongkou District were better, and those located along Bubbling Well Road (now Nanjing Road West) and Avenue Joffre (now Huaihai Road) were the highest.

There used to be what is called the "Upper Corner" and the "Lower Corner" of Shanghai. The "Upper" referred to the best location denoted above, and the "Lower" to the lower and lowest location ranks. The house rent in the two "Corners" could differ as much as four to ten times as much. In the early stages, even Chinese commercial buildings, such as banks, shops or import and export firms, managed by traders from Guangdong and Ningbo, took the form of longtang but on a larger scale. They usually had three or five front rooms on both first and second floors with a courtyard in the middle and back rooms behind. The lower floor was used for business, the upper floor for living, the back rooms in the first floor employee dormitories and the courtyard was used as makeshift storage. It was only during the 1930s, when improvements to business systems were made and many new office buildings were built, that this sort of longtang gradually turned into residential use.